Sayre Gomez

Self Expression

March 19–May 1, 2010

Sayre Gomez creates installations, drawings, and collages that address the most basic formal instincts of art making, born from a practice in which process/form and content are equally important. Gomez had his most recent solo exhibition (2nd Cannons, Los Angeles) in 2009. His work has also been included in the following group exhibitions: The Informant (Curated by Lia Trinka-Browner, JMOCA, Los Angeles), Other People’s Projects (White Columns, New York), The Awful Parenthesis (Curated by Aram Moshayedi, Cirrus Gallery, Los Angeles) and Hard Rain (Kavi Gupta Gallery, Berlin). Self Expression will also act as the title of the artist’s forthcoming exhibition at Kavi Kupta Gallery in Berlin, Germany. Gomez holds degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the California Institute of the Arts.

Gomez’s exhibition continues the gallery's year-long collaboration with writer John Motley. As part of a continued commitment to fostering vital discourse surrounding contemporary art, Fourteen30 Contemporary commissioned recent Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant recipient John Motley to produce a critical essay for each gallery exhibition through the summer of 2010. Each essay appears as part of a limited quantity of offset printed posters, available at the gallery or by request. In an excerpt from his essay on Gomez, Motley writes:

[Gomez] “works in many media, shrugging off the trappings of style, to insistently reiterate a single idea in countless ways, and assert the fragmented nature of identity in the process. As a result, the work in Self-Expression is diverse enough to scan as a group show. In the front gallery, viewers encounter a painting of the brand name “Nike”; a photograph of a photographer, his back turned to the camera, peering through a grey felt curtain; and a photorealistic drawing of an unidentifiable object, perched on a built shelf. Each work is predicated on its interstitial status.

The “Nike” painting, with no iconic swoosh in sight, is clearly not a derivation of the sneaker company’s corporate logo, but it is impossible to think of anything else—certainly not the Greek goddess of victory for which the company is named. The brand name is subjected to several layers of removal, performing a deeper version of appropriation: The logo, usually sewn into fabric, is re-imaged visually and executed as a painting, recasting a mass-produced signifier as a unique, handpainted figure. The “truth-telling” medium of photography captures the photographer at work, but fails to communicate his vision: Everything he sees is concealed behind the curtain. The drawing displayed on the shelf is based on a photograph and, like “Forrest II,” cedes the most central portion of the plane to a rectangle of flat color that practically eats straight through the piece. Here, Gomez’s technical prowess is most evident: The forms in his graphite drawings cannot be identified, but the rich tonality and precise detail suggest facsimile.

Bridging the front gallery with the back, Gomez has applied a layer of bright, banana-yellow paint to an intrusive beam in the first room as well as the walls of the second. The front gallery’s beam is bathed in red light, emphasizing a playful subtext of sexuality in its phallic structure, that one cannot help but see as a foil to the womblike space of the other gallery’s enclosing walls. While the presence of such loud color obviously runs counter to the traditional white cube presentation, the chromatic interplay between the yellow and the rest of the work in the exhibition underscores the relation of perception to expression. After all, every person sees color slightly differently.

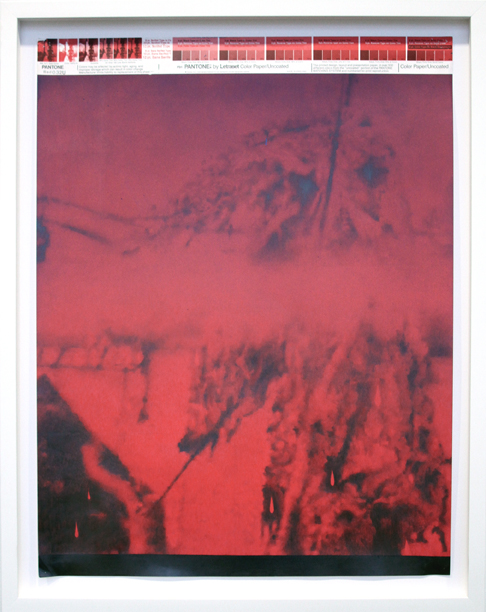

In the back gallery, there are more incongruous objects: two enormous, green-yellow action paintings; a stereo covered in supple blue suede that plays the drunken and deeply idiosyncratic rant of a man outside the artist’s studio; a graphite drawing on vibrant red pantone paper (032U, to be exact); and an oil painting that reads “You lost me at you.” The text from that last piece is important. This work is organized by a logic that is necessarily inaccessible for the viewer: that of the artist. Because the artist cannot express himself in any absolute sense, his meaning—and, by extension, his being— remains unyieldingly inscrutable. In place of the inexpressible self, the artist substitutes metaphor: An avalanche of objects that are like, but unequivocally not.”

Self Expression

March 19–May 1, 2010

Sayre Gomez creates installations, drawings, and collages that address the most basic formal instincts of art making, born from a practice in which process/form and content are equally important. Gomez had his most recent solo exhibition (2nd Cannons, Los Angeles) in 2009. His work has also been included in the following group exhibitions: The Informant (Curated by Lia Trinka-Browner, JMOCA, Los Angeles), Other People’s Projects (White Columns, New York), The Awful Parenthesis (Curated by Aram Moshayedi, Cirrus Gallery, Los Angeles) and Hard Rain (Kavi Gupta Gallery, Berlin). Self Expression will also act as the title of the artist’s forthcoming exhibition at Kavi Kupta Gallery in Berlin, Germany. Gomez holds degrees from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the California Institute of the Arts.

Gomez’s exhibition continues the gallery's year-long collaboration with writer John Motley. As part of a continued commitment to fostering vital discourse surrounding contemporary art, Fourteen30 Contemporary commissioned recent Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant recipient John Motley to produce a critical essay for each gallery exhibition through the summer of 2010. Each essay appears as part of a limited quantity of offset printed posters, available at the gallery or by request. In an excerpt from his essay on Gomez, Motley writes:

[Gomez] “works in many media, shrugging off the trappings of style, to insistently reiterate a single idea in countless ways, and assert the fragmented nature of identity in the process. As a result, the work in Self-Expression is diverse enough to scan as a group show. In the front gallery, viewers encounter a painting of the brand name “Nike”; a photograph of a photographer, his back turned to the camera, peering through a grey felt curtain; and a photorealistic drawing of an unidentifiable object, perched on a built shelf. Each work is predicated on its interstitial status.

The “Nike” painting, with no iconic swoosh in sight, is clearly not a derivation of the sneaker company’s corporate logo, but it is impossible to think of anything else—certainly not the Greek goddess of victory for which the company is named. The brand name is subjected to several layers of removal, performing a deeper version of appropriation: The logo, usually sewn into fabric, is re-imaged visually and executed as a painting, recasting a mass-produced signifier as a unique, handpainted figure. The “truth-telling” medium of photography captures the photographer at work, but fails to communicate his vision: Everything he sees is concealed behind the curtain. The drawing displayed on the shelf is based on a photograph and, like “Forrest II,” cedes the most central portion of the plane to a rectangle of flat color that practically eats straight through the piece. Here, Gomez’s technical prowess is most evident: The forms in his graphite drawings cannot be identified, but the rich tonality and precise detail suggest facsimile.

Bridging the front gallery with the back, Gomez has applied a layer of bright, banana-yellow paint to an intrusive beam in the first room as well as the walls of the second. The front gallery’s beam is bathed in red light, emphasizing a playful subtext of sexuality in its phallic structure, that one cannot help but see as a foil to the womblike space of the other gallery’s enclosing walls. While the presence of such loud color obviously runs counter to the traditional white cube presentation, the chromatic interplay between the yellow and the rest of the work in the exhibition underscores the relation of perception to expression. After all, every person sees color slightly differently.

In the back gallery, there are more incongruous objects: two enormous, green-yellow action paintings; a stereo covered in supple blue suede that plays the drunken and deeply idiosyncratic rant of a man outside the artist’s studio; a graphite drawing on vibrant red pantone paper (032U, to be exact); and an oil painting that reads “You lost me at you.” The text from that last piece is important. This work is organized by a logic that is necessarily inaccessible for the viewer: that of the artist. Because the artist cannot express himself in any absolute sense, his meaning—and, by extension, his being— remains unyieldingly inscrutable. In place of the inexpressible self, the artist substitutes metaphor: An avalanche of objects that are like, but unequivocally not.”