Notions 1, 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

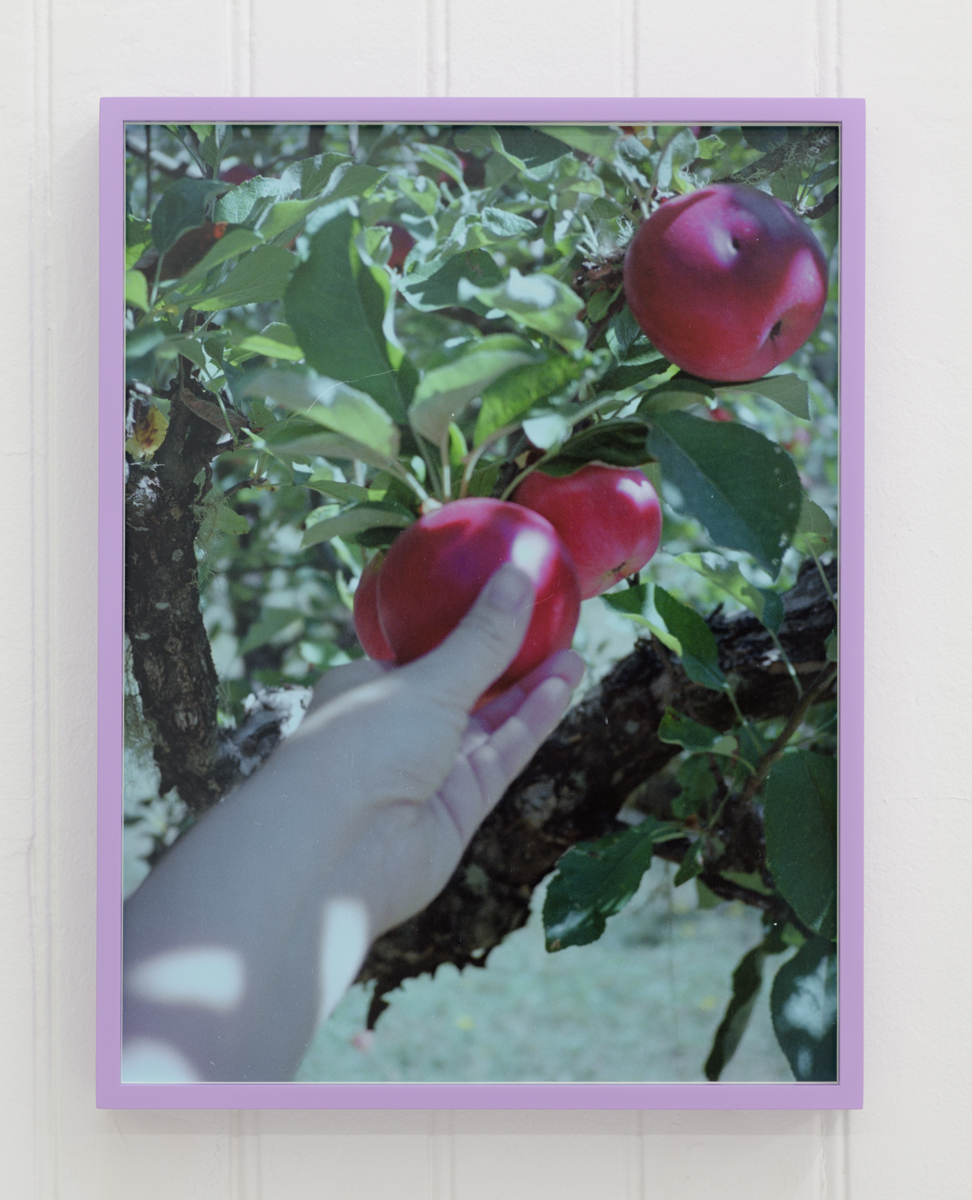

An apple for Amy, 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Notions 3, 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Camera (self-portrait), 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Silver dress (self-portrait), 1994/2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Fan (self-portrait), 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Long Beach, WA, 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Fishnet (self-portrait), 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Girls (self-portrait), 1996/2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Notions 2, 2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Miss Piggy, 1989/2020

archival inkjet print

16 x 12 inches

Edition of 2 / 1 AP

Melanie Flood

Notions

October 3 - November 28, 2020

“If you were going to survey your life, where would you begin? What evidence would you allow into the record, and who might you share it with? As I made my way around the gallery of Fourteen 30 Contemporary to view Melanie Flood’s Notions, such questions kept pinballing around in my head. What is a self-portrait? What is a self?

For many women, defining self is a complicated proposition at best: Trained by society (in ways both infinitesimally subtle and crushingly obvious) to be “nice” and to put others’ needs ahead of our own, self is largely defined by what people want from us. Since these expectations are normalized from early childhood onward, some of us live for three or four decades before we even realize the extent to which we’ve been the subjects—rather than the agents—of our various trajectories. It’s through this lens that I find myself relating to Flood’s photographs, feeling the vulnerability of the artist and the history that I imagine for her, and associating it with my own stories.

The eleven photographs on view, all sixteen by twenty inches and all 2020, are arranged like a slideshow: hung around the room at regular intervals, they give the whole affair a staccato rhythm. As I stepped in front of each new image, I imagined the voice of the artist narrating the display: “Here I am,” click, “This was me in 1996,” click, and so forth. This strategy feels appropriate: when we take stock of our present selves, we often look backward to certain specific moments that changed the directions of our lives—some wonderful, others miserable.

Here Flood’s images are further linked to a particularly feminized/domestic space by her decision to enclose them in frames of bright, uncomplicated lavender—the color of molded plastic baubles from the “Girls” section of a big-box toy store. These are a woman’s pictures, but they are indelibly stamped by the experiences of girlhood. The first image in the sequence, Notions 1, feels like a cryptographic key by which the exhibition could be deciphered. A re-photographed image, it shows a white woman’s beige-manicured hand reaching around a door to place a lavender tag reading “How to Get More Privacy” on the doorknob. The photo reads less like a gesture of Pictures Generation appropriation and more like evidence documented in situ for forensic analysis. The color of the tag matches that of the frames, implying a connection between the show’s framing and privacy. The gesture is one of vacillation between concealment and disclosure, as if trying to control how—and how much—to expose; a fluctuation that reappears through the exhibition.

Other coded images follow: An Apple for Amy (self portrait) shows another white woman’s hand picking a sun-dappled apple from a tree, a direct reference to the garden of Eden fable, which scapegoats women for exile from paradise. Notions 3 depicts a heart-shaped cushion coming apart at the seams; positioned alongside some sparkly fabric, partly shadowed by black transparent material, it’s the photo of an emo teen symbolizing how bruised they are by the world. Miss Piggy, 1989/2020 features a partial view of a room with a framed poster of the Muppets character on the wall, crowned and caped in a royal pose. Also visible are a heart-shaped switch plate and the head of a doll, symbols that abjectly evoke childhood and a stereotypically gendered space. Is the filter one of nostalgia, or regret?

A re-photographed image, it shows a white woman's beige-manicured hand reaching around a door to place a lavender tag reading "How to Get More Privacy" on the doorknob. A white woman's hand picking a sun-dappled red apple from a tree. The most unguarded works in the exhibition are of Flood herself, in five self-portraits that anchor the show, and which feel naked in the sense of being both bare-skinned and exposed. Notions 4 brings the artist into view, albeit in an enigmatic way: Flood’s nude self-portrait is distorted, a mylar reflection that produces the ludicrous exaggerations of a fun-house mirror as well as a strange rippled effect. In such a reflection, the self is rendered indecipherable.

By comparison, the adjacent Notions 5 is filled with specificity. A rack of cassette tapes places the image firmly in the past; wall-to-wall carpet, a cheap plastic chair, louvered closet doors, and clothes on the floor establish its socioeconomic conditions. Amidst the clutter, Flood’s mid-90s self stands in a silver dress and white patent high-heeled slides, regarding the camera knowingly with one hand on her hip. The documentary-like frankness of this image—its borrowed sophistications and dress-up aspirations—feels more raw than the scrambled self-portrait in Notions 4. On another wall, Fan (self-portrait) coyly places the unclothed artist partly behind a large floral curtain, fan in hand, so that she is both concealed and revealed. In Fishnet (self-portrait) we see Flood from behind, dressed in white tights and black fishnet-band bra. There’s a certain honesty here that’s absent in the other self-portraits: a glimpse of armpit hair; pale flesh; incipient wrinkles. This is a body that is beginning to age, earning its stretched, liberated pose but still confined by the conventional trappings of femininity. We see photographer Melanie Flood from behind, dressed in white tights and black fishnet-band bra. There's a certain honesty here that's absent in the other self-portraits: a glimpse of armpit hair; pale flesh; incipient wrinkles. This is a body that is beginning to age, earning its stretched, liberated pose but still confined by the conventional trappings of femininity.

But it was Girls (self-portrait) that magnetized and held my gaze. On the steps of an institutional-looking edifice, below a columned portico labeled GIRLS, sits Flood, perhaps in her very early 20s. Her face, with eyes closed, gives nothing away, but her leaning-forward posture, with arms tucked tightly between her thighs, reads as self-protective. On the wall behind her is a fallout shelter sign. All women have pictures of themselves like this, captured in the process of becoming someone else—a moment both prosaic and profound. Novels could be written about photos like this one, populated with young women (or girls, as the sign would have it) who think themselves adult and thus strong, in reality quite achingly unprotected. I wonder about that building, that person, that shelter, that time—was it as safe a haven as it claimed?

We see ourselves, and the world, from circumscribed perspectives informed by race, class, gender, and a host of other social categories. A permanent, established self isn’t possible, of course, because a self is a fiction that’s continually being revised on the fly. The images Flood has created for Notions suggest a changing self located within a difficult but perhaps all too common history, at once revealed and withheld”

- Documenting the Changing Self: Melanie Flood at Fourteen30 Contemporary

by Bean Gilsdorf for Variable West. November 2020

Notions

October 3 - November 28, 2020

“If you were going to survey your life, where would you begin? What evidence would you allow into the record, and who might you share it with? As I made my way around the gallery of Fourteen 30 Contemporary to view Melanie Flood’s Notions, such questions kept pinballing around in my head. What is a self-portrait? What is a self?

For many women, defining self is a complicated proposition at best: Trained by society (in ways both infinitesimally subtle and crushingly obvious) to be “nice” and to put others’ needs ahead of our own, self is largely defined by what people want from us. Since these expectations are normalized from early childhood onward, some of us live for three or four decades before we even realize the extent to which we’ve been the subjects—rather than the agents—of our various trajectories. It’s through this lens that I find myself relating to Flood’s photographs, feeling the vulnerability of the artist and the history that I imagine for her, and associating it with my own stories.

The eleven photographs on view, all sixteen by twenty inches and all 2020, are arranged like a slideshow: hung around the room at regular intervals, they give the whole affair a staccato rhythm. As I stepped in front of each new image, I imagined the voice of the artist narrating the display: “Here I am,” click, “This was me in 1996,” click, and so forth. This strategy feels appropriate: when we take stock of our present selves, we often look backward to certain specific moments that changed the directions of our lives—some wonderful, others miserable.

Here Flood’s images are further linked to a particularly feminized/domestic space by her decision to enclose them in frames of bright, uncomplicated lavender—the color of molded plastic baubles from the “Girls” section of a big-box toy store. These are a woman’s pictures, but they are indelibly stamped by the experiences of girlhood. The first image in the sequence, Notions 1, feels like a cryptographic key by which the exhibition could be deciphered. A re-photographed image, it shows a white woman’s beige-manicured hand reaching around a door to place a lavender tag reading “How to Get More Privacy” on the doorknob. The photo reads less like a gesture of Pictures Generation appropriation and more like evidence documented in situ for forensic analysis. The color of the tag matches that of the frames, implying a connection between the show’s framing and privacy. The gesture is one of vacillation between concealment and disclosure, as if trying to control how—and how much—to expose; a fluctuation that reappears through the exhibition.

Other coded images follow: An Apple for Amy (self portrait) shows another white woman’s hand picking a sun-dappled apple from a tree, a direct reference to the garden of Eden fable, which scapegoats women for exile from paradise. Notions 3 depicts a heart-shaped cushion coming apart at the seams; positioned alongside some sparkly fabric, partly shadowed by black transparent material, it’s the photo of an emo teen symbolizing how bruised they are by the world. Miss Piggy, 1989/2020 features a partial view of a room with a framed poster of the Muppets character on the wall, crowned and caped in a royal pose. Also visible are a heart-shaped switch plate and the head of a doll, symbols that abjectly evoke childhood and a stereotypically gendered space. Is the filter one of nostalgia, or regret?

A re-photographed image, it shows a white woman's beige-manicured hand reaching around a door to place a lavender tag reading "How to Get More Privacy" on the doorknob. A white woman's hand picking a sun-dappled red apple from a tree. The most unguarded works in the exhibition are of Flood herself, in five self-portraits that anchor the show, and which feel naked in the sense of being both bare-skinned and exposed. Notions 4 brings the artist into view, albeit in an enigmatic way: Flood’s nude self-portrait is distorted, a mylar reflection that produces the ludicrous exaggerations of a fun-house mirror as well as a strange rippled effect. In such a reflection, the self is rendered indecipherable.

By comparison, the adjacent Notions 5 is filled with specificity. A rack of cassette tapes places the image firmly in the past; wall-to-wall carpet, a cheap plastic chair, louvered closet doors, and clothes on the floor establish its socioeconomic conditions. Amidst the clutter, Flood’s mid-90s self stands in a silver dress and white patent high-heeled slides, regarding the camera knowingly with one hand on her hip. The documentary-like frankness of this image—its borrowed sophistications and dress-up aspirations—feels more raw than the scrambled self-portrait in Notions 4. On another wall, Fan (self-portrait) coyly places the unclothed artist partly behind a large floral curtain, fan in hand, so that she is both concealed and revealed. In Fishnet (self-portrait) we see Flood from behind, dressed in white tights and black fishnet-band bra. There’s a certain honesty here that’s absent in the other self-portraits: a glimpse of armpit hair; pale flesh; incipient wrinkles. This is a body that is beginning to age, earning its stretched, liberated pose but still confined by the conventional trappings of femininity. We see photographer Melanie Flood from behind, dressed in white tights and black fishnet-band bra. There's a certain honesty here that's absent in the other self-portraits: a glimpse of armpit hair; pale flesh; incipient wrinkles. This is a body that is beginning to age, earning its stretched, liberated pose but still confined by the conventional trappings of femininity.

But it was Girls (self-portrait) that magnetized and held my gaze. On the steps of an institutional-looking edifice, below a columned portico labeled GIRLS, sits Flood, perhaps in her very early 20s. Her face, with eyes closed, gives nothing away, but her leaning-forward posture, with arms tucked tightly between her thighs, reads as self-protective. On the wall behind her is a fallout shelter sign. All women have pictures of themselves like this, captured in the process of becoming someone else—a moment both prosaic and profound. Novels could be written about photos like this one, populated with young women (or girls, as the sign would have it) who think themselves adult and thus strong, in reality quite achingly unprotected. I wonder about that building, that person, that shelter, that time—was it as safe a haven as it claimed?

We see ourselves, and the world, from circumscribed perspectives informed by race, class, gender, and a host of other social categories. A permanent, established self isn’t possible, of course, because a self is a fiction that’s continually being revised on the fly. The images Flood has created for Notions suggest a changing self located within a difficult but perhaps all too common history, at once revealed and withheld”

- Documenting the Changing Self: Melanie Flood at Fourteen30 Contemporary

by Bean Gilsdorf for Variable West. November 2020